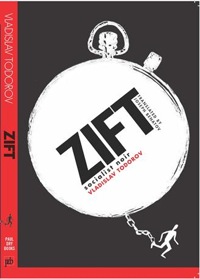

Imagine the TV thriller series 24 cross-bred with Orwell’s dystopian classic 1984 and a dose of absurdist theater, and you’ll conjure up the mood of Vladislav Todorov’s novel Zift, published in 2010 by Paul Dry Books and translated by Joseph Benatov. Its hero and narrator, a philosophical thief named Moth, entered prison for a murder he didn’t commit just before Bulgaria went communist (with strong-armed help from the USSR) in 1944. He emerges on December 21, 1963, to a totalitarian world and is immediately poisoned by his former partner in crime, Slug, who wants to locate the diamond that Moth supposedly stole before he was imprisoned.

Imagine the TV thriller series 24 cross-bred with Orwell’s dystopian classic 1984 and a dose of absurdist theater, and you’ll conjure up the mood of Vladislav Todorov’s novel Zift, published in 2010 by Paul Dry Books and translated by Joseph Benatov. Its hero and narrator, a philosophical thief named Moth, entered prison for a murder he didn’t commit just before Bulgaria went communist (with strong-armed help from the USSR) in 1944. He emerges on December 21, 1963, to a totalitarian world and is immediately poisoned by his former partner in crime, Slug, who wants to locate the diamond that Moth supposedly stole before he was imprisoned.

Within this film noir framework, using the poison in Moth’s body as a literal “ticking clock,” Todorov takes us on a kaleidoscopic tour of Sofia, Bulgaria’s capital city, through the eyes of a man who has never seen communism and must learn his former world anew. In its most shining moments, Zift—which literally means a bituminous tar used to fix asphalt and occasionally as chewing gum—seamlessly blends its thriller aspect with socialist cultural critique.

Prior to its U.S. publication, Zift was adapted into a movie (with Todorov as screenwriter); HBO airtime made it the most broadly released Bulgarian film to reach American shores. Todorov and translator Benatov both teach at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

Conversation

Steven Wingate: Most historical novels have some kind of resonance with the contemporary world in which they are read. Why is now the right time for Zift to come out? Why was it important for you to write it?

Vladislav Tordorov: The reason is complex. It concerns my personal fascination with the [historical fiction] genre itself. Also, it has much to do with the state of Bulgarian post-communist fiction. And it concerns the fictional representation of the communist past in Bulgaria today when we have conflicting versions of this past.

Novels talk to other novels, not only to the real world. Thus, they position themselves within various literary contexts. Bulgarian post-communist fiction of the 90s demonstrates a consistent “lyrical” approach—fictional reflections of a rather intimate and strictly personal, even idiosyncratic nature. Under communism novelists had to be markedly aware of their social and political environment, and [they had] to follow strict guidelines of its representation—the so-called “socialist realism.” After the fall of communism, they could engage in soul-searching, which led to the “lyrical novel.” This type of novel lacks eventful storyline and refrains from discussing social issues. The same goes for Bulgarian cinema, which at the time amalgamated personal frustrations and idiosyncrasies with folklore imagery and poetical fabulousness. Within such literary and cinematic contexts, my task was to create a type of narrative that would be both lyrical (Zift’s story is told in the form of a confession), and genre-and-plot driven (it consciously adopts the hardboiled style of noir). In recent years many plot-driven novels have been published in Bulgaria. In this respect Zift joins a new wave of narrative fiction.

Novels talk to other novels, not only to the real world. Thus, they position themselves within various literary contexts. Bulgarian post-communist fiction of the 90s demonstrates a consistent “lyrical” approach—fictional reflections of a rather intimate and strictly personal, even idiosyncratic nature. Under communism novelists had to be markedly aware of their social and political environment, and [they had] to follow strict guidelines of its representation—the so-called “socialist realism.” After the fall of communism, they could engage in soul-searching, which led to the “lyrical novel.” This type of novel lacks eventful storyline and refrains from discussing social issues. The same goes for Bulgarian cinema, which at the time amalgamated personal frustrations and idiosyncrasies with folklore imagery and poetical fabulousness. Within such literary and cinematic contexts, my task was to create a type of narrative that would be both lyrical (Zift’s story is told in the form of a confession), and genre-and-plot driven (it consciously adopts the hardboiled style of noir). In recent years many plot-driven novels have been published in Bulgaria. In this respect Zift joins a new wave of narrative fiction.

Another aspect of Zift concerns the communist past. I have written extensively on this issue—essays, journalism as well as scholarly papers. Zift is my literary attempt to address it. Back in the 90s there were few novels that would deal with this past, although the situation has changed recently. The past that was ripping apart the nation in the public arena was generally ignored by fiction. In many respects this past defines the present state of affairs in Bulgaria, the common attitudes, the popular imagination, the public reflex.

Does Zift point toward any particular precedents outside of Bulgarian literature?

Does Zift point toward any particular precedents outside of Bulgarian literature?

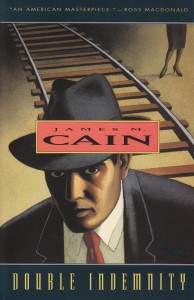

I wrote Zift as an indirect tribute to James Cain‘s Double Indemnity and The Postman Always Rings Twice. In these novels the narrator confesses to his crimes. I find Cain’s books much more interesting than Hammett’s or Chandler’s, wherein a private eye narrates while trying to crack a case. The criminal narrator is decidedly more fascinating than the private eye. I should also mention that Postman had a direct influence on Camus when he was writing The Stranger and on Visconti’s debut feature Ossessione that pioneered the Italian neorealism.

In your writing process, how did you balance the “socialist” and the “noir” aspects of the book? Did you always have a unified sense of how they would work together, or did that shift over time and fall into place in revision?

Zift draws on personal experiences—my early days of growing up in a communist country in the 60s and my later days of teaching fiction and film at Penn. So, I decided to couple my early memories and late intellectual pursuits in a novel.

In the Bulgarian literary tradition and its contemporary cinematic context the genre of noir is an exotic animal. On the other hand, in the American eye, the socialist content makes the classical genre of noir appear curiously estranged. This is probably why the movie Zift enjoys its highest critical acclaim and audience recognition in Russia and in the U.S.—the respective birthplaces of the socialist content and of the genre form. The form and the content are in a subtle way alien to each other. According to Russian critic Viktor Shklovsky, this is what makes a work of art function effectively and become aesthetically pleasurable. He calls it “estrangement” or “de-familiarization” of the familiar. It is the result of the unusual coupling of form and content. The idea was to “unlock” the social reality of communism with a seemingly strange genre key, and vice-versa—to reinvent the political aesthetics of the genre by populating it with communist imagery. The clichés clash—these of the communist content and those of the noir form.

In the midst of following Moth through his adventures, you also give us moments that seem outside of time, in which people engage in circuitous philosophical debates, trade urban legends, etc. What were you going for in such scenes, and is there a unity of purpose for them throughout the book?

In the past, urban legends and popular anecdotes used to serve as potent antidotes against the daily dose of toxic communist demagogy fed to the public through various communication channels. The former were works of a collective anonymous countercultural genius that effectively resisted the official culture controlled by the Party. The urban lingo and legendary stories that the counterculture spontaneously and indiscriminately proliferated in effect subverted the official Party-speak, along with all the newspaper feature stories of shock-workers and mass exploits in the line of collective farming and industrial production. Vulgar philosophizing and anecdotal storytelling, the raw Pravda (truth) of life shared by outcasts, lowlife, barflies, and local idiots in the dark pockets of the city spectacularly outshouted the authoritarian, officially forged Pravda. The communist “speak” and its adversary—the countercultural lingo—presented a real challenge for the English translation, and I am glad to say that in my view, Joseph Benatov has done a great job.

In the past, urban legends and popular anecdotes used to serve as potent antidotes against the daily dose of toxic communist demagogy fed to the public through various communication channels. The former were works of a collective anonymous countercultural genius that effectively resisted the official culture controlled by the Party. The urban lingo and legendary stories that the counterculture spontaneously and indiscriminately proliferated in effect subverted the official Party-speak, along with all the newspaper feature stories of shock-workers and mass exploits in the line of collective farming and industrial production. Vulgar philosophizing and anecdotal storytelling, the raw Pravda (truth) of life shared by outcasts, lowlife, barflies, and local idiots in the dark pockets of the city spectacularly outshouted the authoritarian, officially forged Pravda. The communist “speak” and its adversary—the countercultural lingo—presented a real challenge for the English translation, and I am glad to say that in my view, Joseph Benatov has done a great job.

Your uses of Wired Radio Outlet—Muzak-like songs often playing in the background—strike me as places where “socialist” and “noir” blend seamlessly. It’s creepy and Big Brother-ish, but at the same time your characters respond to it and even let the songs shape their behavior. What does Wired Radio Outlet mean to you, and what do you want it to mean to readers?

The Wired Radio Outlet brings back personal memories of many places and events. The everyday world around us was all wired. It was virtually everywhere—in schools, public baths, hospitals, etc. In the novel, the Wired Radio Outlet has a structural function. It measures the flight of time. It announces the exact time on a regular basis and thus serves the purpose of a public clock. The action deploys in one freezing December night, the longest night of the year. Time runs fast like sand in an hourglass, and Moth runs out of it as we read along.

You also wrote the screenplay for Zift, which did very well internationally and was shown in the U.S. on HBO even before the English translation was released. How did you approach and manage that process? What does the story of Moth gain and lose in its translation from fiction into film?

Noir films are based on pulp fiction. So, in an effort to keep the tradition, I worked on the novel and the script simultaneously. I should point out that in the movie, the story has a different ending, which I thought was more dramatic for the viewer. In fact, the English version of Zift has the movie ending.

What did you learn from Zift that you’ll bring to your next fiction project? And do you mind telling us what that project is?

Yes, it is called Zincograph. The novel was published in Bulgaria last summer, and the script is in an early stage of production. Hopefully we could see it filmed by 2012. The story is about a cunning young man who becomes an informant for the Bulgarian communist secret police. He does his job with a great zeal, and yet he is dismissed, as Perestroika renders him useless. Spying and denouncing is his true vocation, so he decides to continue his activities secretly from the government. He creates his own phantom secret police department by recruiting a group of unsuspecting young intellectuals to spy on each other. As a result, he develops his own secret archive of denunciations and, after the fall of communism, benefits from that.

Yes, it is called Zincograph. The novel was published in Bulgaria last summer, and the script is in an early stage of production. Hopefully we could see it filmed by 2012. The story is about a cunning young man who becomes an informant for the Bulgarian communist secret police. He does his job with a great zeal, and yet he is dismissed, as Perestroika renders him useless. Spying and denouncing is his true vocation, so he decides to continue his activities secretly from the government. He creates his own phantom secret police department by recruiting a group of unsuspecting young intellectuals to spy on each other. As a result, he develops his own secret archive of denunciations and, after the fall of communism, benefits from that.

Zincograph is a black comedy with elements of political psycho-thriller that draws on the very nature of secret policing under communism—the presumed authenticity of the agents and recruitment based on automatic trust and unspoken fear. The plot is driven by the workings of the conspiratorial mind of an overzealous conformist-turned-psychopathic schemer and wicket social engineer. The purpose of this story is to debunk the commonly shared assumption that totalitarianism is a society of victims and victimizers. I submit that many people enjoyed spying on their neighbors, took pleasure in it and pursued it proactively. Declassified archives show that on many occasions we dealt with true zeal on the part of the informants, who didn’t simply follow instructions, but demonstrated maleficent eagerness to “develop” harmful information regarding the lives of others.

How does Zincograph’s dark humor compare to the dark humor of Zift?

The “black laughter” in the two novels is of a different nature. The action takes place on historical thresholds—before and after the imposition of communism (Zift) and before and after its collapse (Zincograph). These events could be viewed as collective somersaults or tragicomic stunts in the political circus of their own times—jumping in and out of communism. The aim was to frame the two jumps differently in terms of genre, plot and antiheroes, but to keep their tragicomic representation. Zift is a confessional narrative delivered by a man who recounts his misfortunate life and badly failed intentions while facing his ultimate demise. Moth defies death by means of unrelenting existentialist irony—the battering ram of wit. His sharp aphoristic attitude towards the communist world demystifies it.

This should have a redeeming effect on both him and the reader. Contrastingly, Zincograph tells the story of a con artist who social-engineers a fake political institution that replicates and thus mocks the omnipotent system of secret police. The mimicking of the untouchable system, its shadowy doubling is subversively farcical, is diabolically comical by nature. A bold political con is launched by a seemingly ridiculous man. His creation becomes the Trojan horse, which eventually disorganizes the system by making it function like one stupendous lampoonery. In both novels, the machinery of laughter vandalizes two formidable representations of the Absurd—the fact of Death and the fact of the System.